Dispatches from afar

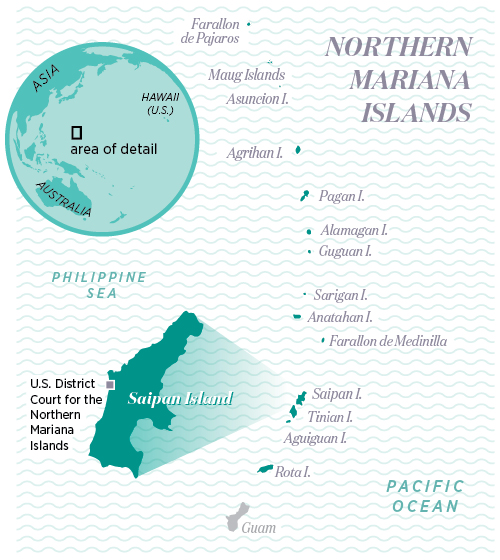

No one arrives at the Northern Mariana Islands by accident. A commonwealth of the United States, this group of small islands in the western North Pacific lies roughly 3,800 miles west of Hawaii, 1,600 miles east of the Philippines, and 1,500 miles south of Japan. It’s 14 time zones from Virginia and takes more than a day’s worth of travel to reach from Richmond.

When Albert “Bubba” Flores, L’16, became an assistant U.S. attorney for the District of the Northern Mariana Islands in January 2021, it was a noteworthy destination for him in more than geographical terms. After serving as a criminal prosecutor for the city of Richmond for five years, Flores would now practice law at the federal level. The new role drew on — and yet was in stark contrast to — his four deployments with the Marine Corps in Iraq and Afghanistan over a decorated 19-year military career. And, after a recent 15-month deployment apart, it was an ideal opportunity for his young family of five to reconnect as they together explored their new home.

Called to do something noble

As a kid growing up in San Jose, California, Flores was intrigued by the military. When he was 6 or 7, he attended a county fair and visited each branch’s recruitment booth. The Army booth impressed him with an actual tank and guns on display; the Navy recruiter offered bumper stickers and posters. “When I got to the Marines booth,” Flores recalled, “there were only three Marines in dress uniform, a pull-up bar, and bumper stickers. I asked if I could have a sticker and the recruiter said, ‘No. Nothing is free in the Marine Corps. You have to do two pull-ups to get a sticker.’”

Heartbroken, Flores figured he’d never be good enough to join the Marines. More than 10 years later, during his freshman orientation at Washington State University, a conversation with a Navy recruiter convinced him that becoming a Marine was not only attainable but appealing: He could expand his skills, serve his country, and do something “noble,” as Flores puts it. He joined the ROTC on campus, completed Marine Corps Officer Candidates School in 2002, then started active service after graduating in 2003. In college, he met his wife of 17 years, Doemiko. “I had a shaved head and was very gung-ho,” Flores said. “So she knew from the beginning that if she married me, she was marrying the Marines.”

A defining moment

Flores is often asked — especially by younger service members — about his combat experiences during his deployments to Iraq (2005–06 and 2007–08) and Afghanistan (2009). He describes his first Iraq tour as “the Wild West — a chaotic time.” Foreign fighters were pouring into Iraq to join loyalists and other Iraqi insurgents in fighting against American and coalition forces. Every day brought gunfights, roadside bombs, and airstrikes, he said, “each with tragic and violent results.”

By his second tour, he was a platoon commander in charge of 23 Marines tasked with reconnaissance missions — a lot of responsibility for someone just 25 years old.

His 2009 deployment to Afghanistan was a year of tremendous loss and personal growth. It was an inflection point that marked a “before” and “after” in his life. On his first mission, an IED explosion hit a vehicle providing navigation for a convoy Flores commanded. The explosion killed two Marines in the vehicle, including Flores’ best friend, Master Sgt. John E. Hayes. They had just served together in Iraq. “John was the most highly revered and respected recon Marine in our company,” said Flores, who still keeps in touch with the wife and three children Hayes left behind.

Yet it was another incident that Flores says “defined me as a person”: when he led his reconnaissance company on a perilous nighttime raid in Taliban-contested Helmand province. It was the last mission of his deployment, with the goal of interdicting a Taliban cell. The mission was successful, but it took longer than expected to extract the captured Taliban members and sort through the drugs and weapons at the site. His company’s position was revealed with the rising sun, and for several hours, the Taliban barraged them with rockets and mortars.

American air support arrived to provide cover, and Flores was tempted to continue engaging the enemy forces. But the mission had already achieved its tactical objective, he said, “and surely, the longer we stayed on the ground, the more damage we would have caused to the town, and the more risk of civilian deaths. And the risk to our recon Marines increased every minute we stayed.” Flores made the decision to withdraw.

“I’m proud of that moment,” he said. “It took maturity and wisdom to exercise that type of restraint” — to make decisions that are not about glory but about what’s best for the mission and the personnel. And he’s pretty sure where the wisdom came from: “I know John Hayes was whispering in my ear.”

For his leadership in combat in Helmand province, Flores received the Bronze Star with Valor.

A pivot into law

That two-hour gunfight proved pivotal for Flores’ career as well: It caused him to take a step back and think about the bigger picture. He could be of better service, he decided, if he could be a part of the policymaking decisions — the strategy for how, when, and where to use military force — rather than just being a part of the operations on the ground. He figured a political career might be better for him — and what better way to get into politics than to become a lawyer?

Flores returned to the States and remained on active duty for three more years, serving as a commander within a new intelligence initiative at the Marine Special Operations Command at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina. During that time, he also earned a master’s degree in political science from the online American Military University.

In 2012, he transitioned to the Marine Corps Reserve, and a year later, at the age of 32, he entered the University of Richmond School of Law.

Flores quickly made an impression on campus. He was one of 30 people chosen statewide for the Sorensen Institute’s Political Leaders Program at the University of Virginia; the program focuses on trust and civility in politics. “You learn how to navigate partisanship and how to approach Virginia’s problems,” Flores said. While he enjoyed learning how he could potentially make a difference, he found that he didn’t enjoy the politics — and decided to focus on a courtroom career instead.

Flores, who became a father during law school, also devoted his time to both the Children’s Defense Clinic and the Wrongful Convictions Clinic. “[The latter] was where I learned about court prosecution and the criminal justice system from a perspective I hadn’t previously considered,” he said. “As I approach every single one of my cases now, I look out for investigational pitfalls and recognize when a case should not be prosecuted.”

The campus cause nearest to Flores’ heart was the Veterans and Military Law Association, a support network for veterans and for students interested in becoming military lawyers. As its president, Flores transformed the association from primarily a social organization to one that provides pro bono legal services to veterans seeking disability benefits. He helped build a partnership between the VMLA and the Carrico Center for Pro Bono and Public Service — a partnership that continues to this day.

Just because you can do something doesn't mean you should.

“It remains one of our most consistently resourced programs,” said Tara Casey, director of the Carrico Center. Each week, student volunteers with the center identify pro se veteran claimants on the federal circuit docket. The volunteers draft a case summary that’s shared with the Federal Circuit Bar Association’s pro bono veterans appeal panel, which determines which cases may be appropriate for pro bono representation.

“Any space that he goes into, Bubba impresses everyone with his genuineness and authenticity,” Casey said. “He truly lives and walks his ethos.”

At graduation, Flores received the Charles T. Norman Award, given to the best all-around student, as voted by the faculty. “I was humbled,” he said. “Law school was hard for me as an older student and as a parent. I succeeded only because of my wife and my friends at the law school.”

Duty calls

Flores continued to honor his commitment to the Marine Corps Reserve throughout law school and as he settled into his job as a criminal prosecutor for the city of Richmond. As he tried a wide range of cases — homicides to misdemeanors, firearms offenses to drug cases — he recognized parallels between his legal and military careers. “Military commanders and prosecutors both have so much discretion and so much power,” he said. “Just because you can do something doesn’t mean you should. I applied that principle to try to be the fairest prosecutor I can be.”

In the fall of 2019, three years into his prosecutor role and engrossed in a high-profile murder trial, Flores got a call from his reserve battalion commander. Because of his rank, his special operations intelligence expertise, and his combat experience, Flores would be deployed once again for several months of extensive training followed by a nine-month mission to Afghanistan. It was unexpected: “My wife and three kids were used to me being home all the time except for reserve training,” Flores said. The idea of him being away for more than a year — on two weeks’ notice — caught them off guard. Fortunately, the Richmond legal community rallied around Flores and his family during his deployment, checking in on Doemiko and the children and sending Flores care packages and letters of encouragement.

In Afghanistan, Flores advised Afghan army commanders and was part of a task force training the Afghan military and police for the transition to self-sufficiency. He was awarded a second Bronze Star for meritorious service during the deployment. “I may have gotten the Bronze Star,” he said, “but Doemiko deserves her own award for being married to a deployed Marine and being a mother with three kids at home with COVID going on.”

I hope that ... I can impart wisdom I gained through my experiences.

Practicing federal law in paradise

As his Afghan deployment was winding down in late 2020, Flores was looking ahead to his next chapter. He had decided to pursue a position as a federal prosecutor and found the posting for the Northern Mariana Islands opening. He interviewed for the job via videoconference at 3:30 a.m. Afghanistan time; he had to apologize for wearing his dirty military uniform rather than a business suit.

When he was offered the job, Flores and Doemiko accepted without hesitation, even though they’d have to move half a world away without first seeing their new home on Saipan (the largest island in the Northern Mariana Islands). They knew the opportunity would give them a welcome change in lifestyle after Flores’ deployment. “We are adventurous people,” he said. “We love the ocean. We love boating, diving, and fishing, and that is what Saipan is all about. We sold our home and cars, got rid of as much as we needed to, and we just went all in.”

Flores started his new position in January 2021. He works with two other assistant U.S. attorneys in the new state-of-the-art Saipan branch office. The district’s headquarters are on Guam, about 130 miles to the south, where the U.S. attorney and seven additional assistant U.S. attorneys are based. Flores focuses on criminal cases that cover the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and provides support for Guam cases. He serves as the district’s coordinator for national security and Project Safe Neighborhoods, in which he works with local law and government officials on efforts to reduce violent crime.

Flores started his new position in January 2021. He works with two other assistant U.S. attorneys in the new state-of-the-art Saipan branch office. The district’s headquarters are on Guam, about 130 miles to the south, where the U.S. attorney and seven additional assistant U.S. attorneys are based. Flores focuses on criminal cases that cover the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands and provides support for Guam cases. He serves as the district’s coordinator for national security and Project Safe Neighborhoods, in which he works with local law and government officials on efforts to reduce violent crime.

Flores and the other two federal prosecutors in the CNMI handle a wide variety of cases, with an emphasis on public corruption, drugs, immigration fraud, and white-collar crime. Both Guam and the CNMI see significant cargo ship traffic, which can involve illicit narcotics trafficking.

Immigration fraud cases are also prominent on the docket: The CNMI’s population includes thousands of foreign workers, some of whom are undocumented. The fact that the jurisdiction is geographically closer to countries in southeast Asia — most notably China — than to the mainland U.S. also complicates Flores’ work. Some of what he does has implications for national security, and much of that work is classified.

Fun and family time

Meanwhile, Flores and his family are taking full advantage of Saipan’s many natural treasures. Both avid scuba divers, he and Doemiko have explored the surrounding coral reefs and numerous shipwrecks from World War II. A passionate fisherman, Flores can fish for marlin and wahoo within a five-minute boat ride from shore. On days when it’s too windy to fish, he and a colleague indulge in a new pursuit: kitesurfing. “My kids love to come to the kitesurfing beach and root for us,” he said.

His family time on Saipan with Doemiko and their three children — Miriam, 7, Thomas, 5, and Scarlett, 4 — has been invaluable to Flores. He lives two minutes from his children’s school and five minutes from work. He sometimes drives an ATV rather than a car place to place, including to the local VFW post. He attends his children’s extracurricular activities and coaches Miriam’s soccer team. He can swing home over his lunch break to check in on his family and have lunch with them.

The family is looking forward to exploring a whole new region of the world that’s now at their doorstep — including Hawaii, where Flores (now a lieutenant colonel) reports twice a year for reserve duty.

“My motivation for being in the Marine Corps has evolved over my career,” he said. “Initially, I wanted to see how hard I could push myself. A few years later, it became about brotherhood and love of the guys I was serving with. Then it became a devotion to service and making a difference. Now, I hope that with my current rank and position, I can impart wisdom I gained through my experiences and combat deployments to the newest generation of Marines.”

After years of active duty, combat deployments, grad school, and job changes, Flores knows he has made the right move for his family and his career. And each day, as he looks out his office window at the blue expanse of the Pacific Ocean, he’s fairly certain that no assistant U.S. attorney anywhere else has a better view.